NEWS PHOTO STORIES

“Things that simply won’t let go”

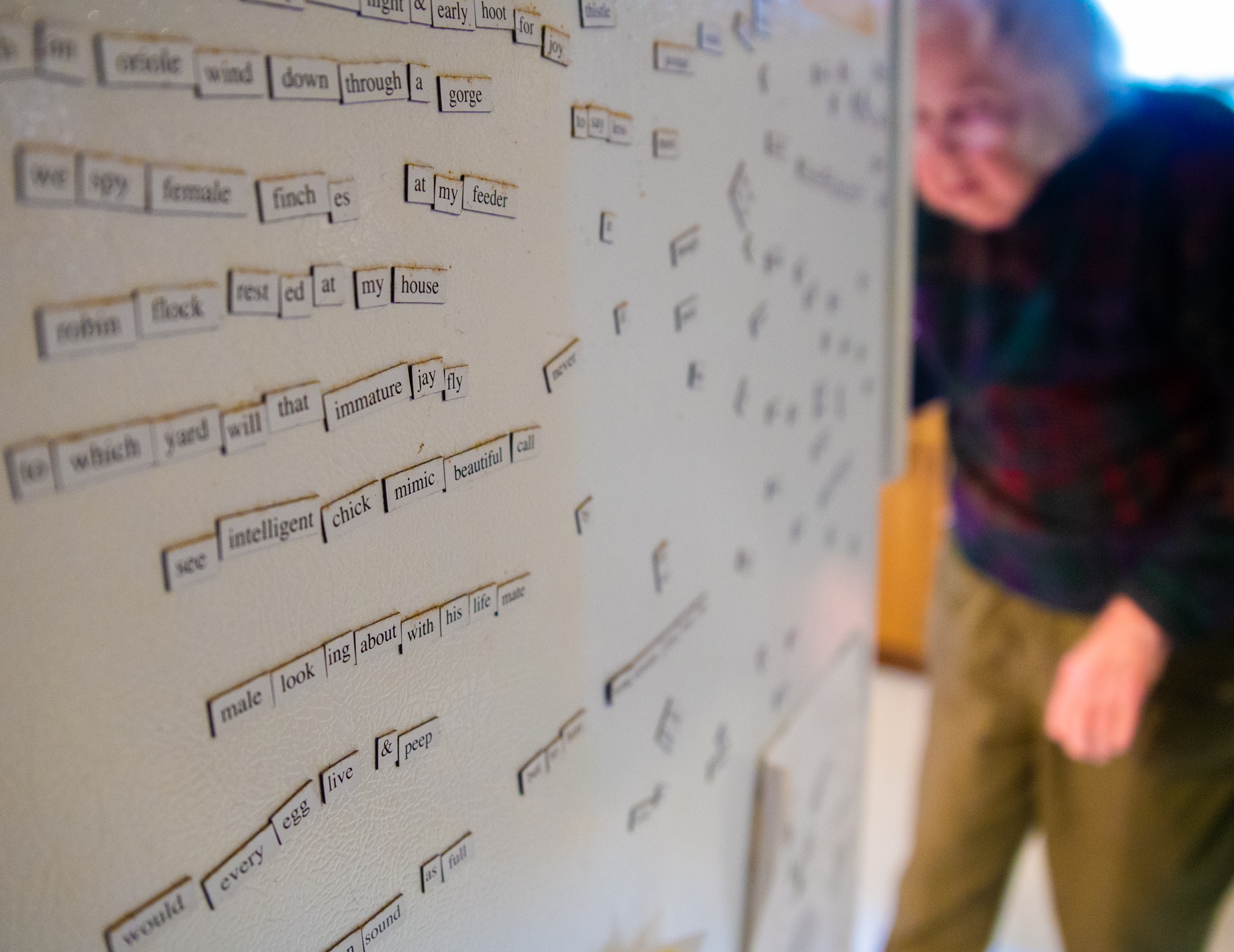

Judy Hogan is an 81-year-old environmental activist, writer, and teacher. Since the 1960s, she has fought a myriad of different environmental justice issues affecting her community in Chatham County, N.C. She is leading a fight against Duke Energy dumping coal ash in her town. She publishes books and poetry and teaches writing classes twice a week.

This series of photos is accompanied by selected poems from Hogan’s most recently published book, called “Shadows”, autobiographical about her daily life. I took a more free-form, artistic approach with this caption style because I want Hogan to speak for herself.

"For me it’s shadows. Every day I walk across

the dam, I watch for my shadow marching

below me, down the hill, and some days,

when the wind is still, even across the water

and up the hill at the other end of the earthen

dam that creates Jordan Lake. In the painting

there is one small human figure surrounded

by rushing water, darkly threatening clouds,

with only a small window of blue that could

be sky but is probably water. That little

shadow is very persistent as she trudges

along. Even in a wind, she doesn’t hesitate,

pulls her hood up to protect her neck and

ears. A step at a time a great distance can

prove possible. But, oh for the courage

to believe in that shadow. I like to think

that when I’m gone, and even if storm clouds

dominate, and water boils and foams, and

wind is cruel and relentless, that my shadow–

all that is left of me and whatever words

on paper survive my death–will keep on

walking with firm steps, seeing more than

I can see now, accepting storms, even

lightning, but refusing to be dismissed,

ignored, or turned aside–something eternal

or stubborn, or so part of the nature of

things that it simply won’t let go."

- From Judy Hogan's original poem book "Shadows"

"How to tell it? I have a new friend

in the midst of my aging, when new

friends are rare. She’s a bird-watcher.

I’m a people-watcher. What I learn,

I scarcely know until I put it in my

books. Some mistrust other people

first and foremost. I attend to them

with my mind open. She talked to

my dog, and Wag listened. Wag is

tolerant now of other people but

skeptical, too. It takes time for her

to trust, but the bird-watcher turned

out to be a dog-whisperer and spoke

Wag’s language, baffling to me. Mind

over matter maybe. Wag would stop,

hesitate, and then touch her nose to

the outstretched hand. Me she pulled

in, too, to tell of the sixteen eagle

nests around our Jordan Lake. I

asked how they would have fared

during our hurricane. She said they

have favorite places to hunker down

during storms, but we had four days

of wind and rain, so she’s checking

on them. She watches for them to

fly by, way up there and catches

them in her camera the way she

caught Wag and me as we walked

toward her, both smiling, she says,"

- From Judy Hogan's original poetry book "Shadows"

"Erik Erikson said Ghandi found his

true identity when he was fifty. I

was seventy, still healthy, writing

and publishing books, teaching writers,

a small farmer with a flock of White

Rock hens, and a leader in my

community. At eighty, I take that

diversity of tasks for granted. I don’t

debate. It is a balancing act, and

my balance ability is distressed

by my age. Still, I rake and dig.

I hold onto tree branches and my

chain-link fence. I’ve said I’m

both Penelope and Odysseus. I

did have my once-in-a-lifetime

love–across the ocean, despite

the language barrier, and our

different lifestyles. We fought,

but we held on. He became one

of Homer’s shades, reduced to

shadows in the Underworld, but

still alive, still speaking and

foretelling the planet’s future if

we don’t attend to the signs. I’ll

be a shade, too, before too many

years have passed. Some of that

is beyond my control, and some

is up to me. The doctors urged

a cane four years ago, but I said

no. “I can’t farm with a cane.”

They said medicine, but I was

wary of the side-effects, the

medicine worse than the complaint.

My body heals while I sleep.

It puts me to sleep a lot. But my

aches and pains go away. I tell

them I have good telemeres.

They listen. The symptoms which

puzzled them have disappeared.

Eighty isn’t so bad if you accept

that your pace will be slower…

No, I’m not a shade yet, and life

still pulls surprises out of my

lucky grab bag. I can’t complain."

- From Judy Hogan's original poem book "Shadows"

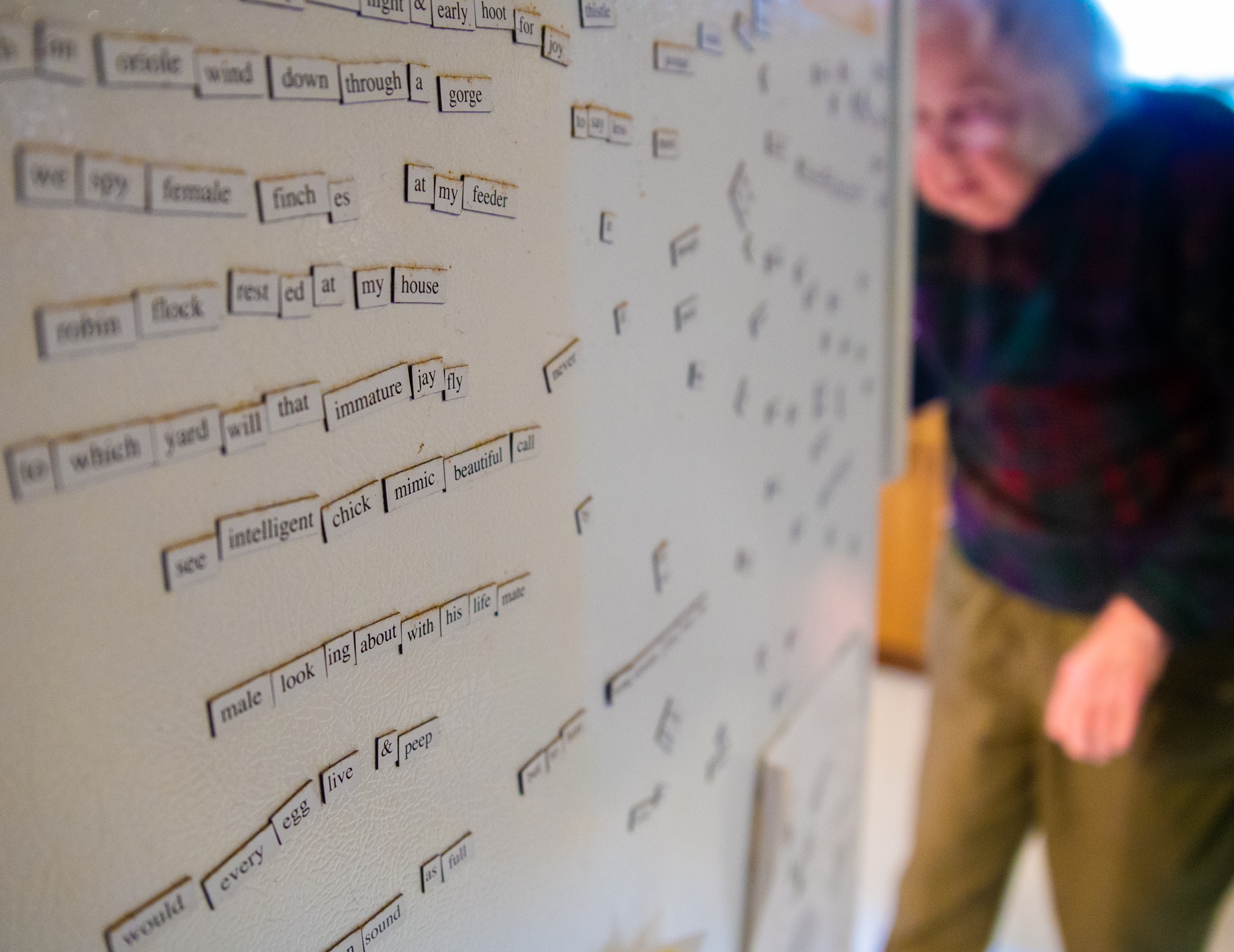

"I was afraid my heart would rebel

and keep me from leading a workshop

on writing poetry. My friend had said

to rest more. I had things to do,

but I did stop to rest. Then six people

came to learn what I knew about

poetry. “What is a poem?” I asked.

They suggested it was condensed

words, that it was like a stream running

through the soul. I told them the

fourth grader’s understanding: “A poet

is someone who writes poetry, someone

who loves all living things.” I told

them about Homer’s Muse, about

the Old Testament prophets who

cried: “The Word of the Lord came

to me.” About how words could seem

to take off, and the deeper mind to

throw up words we weren’t expecting.

I mentioned Jacques Maritain’s hexis–

a gift we have in our unconscious

that we need to take care of and

listen to. If the poem starts in the

grocery store, make more room

in your life for the Muse. Then I

asked them to write a simple poem,

and they all did, even the librarian.

To my surprise, they all read their

new poems. They trusted me and

each other enough on very short

acquaintance. My heart behaved and

was quieted. Another unexpected gift."

- From Judy Hogan's original poem book "Shadows"

"Some see the world as a dangerous place.

I don’t. One says, “You see it as a safe place.”

I say, “No, but I see it differently. I know

there are dangers, but I’m focused on trying

to be in tune with the grain of the universe,

with the way it’s made. I follow my deep

intuition, even when it doesn’t make sense.

It makes me accident-unlikely. I may have

accidents, but usually they’re not as bad as

they could have been. So, yes, I had that flat

tire on Thursday, but it happened in my

front yard. I drove it across the road and

turned. When it was still bad, I pulled over

and stopped to look. I had a very flat right

front tire. Or I have car trouble as I pull into

a service station. I work toward peace

with my neighbors and fight for all of us

for cleaner air and water. They respect me

and protect me. I’ve never been harmed

by my neighbors, and I’ve often been

helped. You don’t need to worry about them

harming me.” I have a very different

orientation to the world. There are dangers

and evil people. If people are determined

to be my enemy, I stay away from them.

In the meantime, I try to have friendly

relations with everyone, if it’s possible. I’m

outspoken, and some people hate what I say

and can’t forgive me. One day I might be

harmed, but this way to live suits me."

- From Judy Hogan's original poetry book "Shadows"

"Resting is hard for me. I have so much

I want to do before Shadows take me

from this life. Maybe

I don’t need to be so inactive. Can

I let go fear, slow myself down but

not stop, not let fear put its claws

into my soul, my trust that, if I pay

attention, all will be well."

- From Judy Hogan's original poetry book, "Shadows"

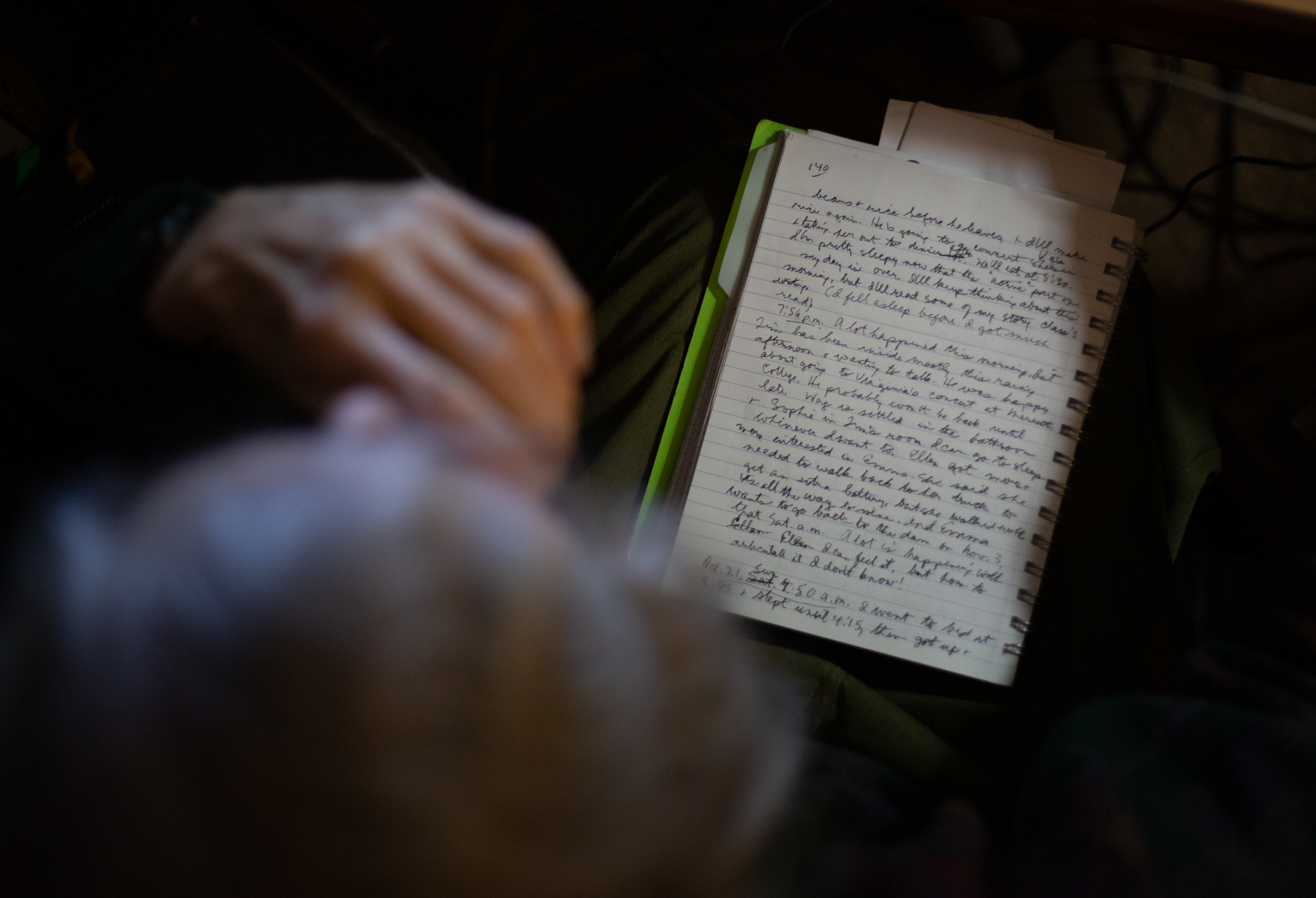

"Beginnings are hardest. In the morning

I sit up slowly, inch my way closer

to a place to hold on, rise carefully,

balance before I walk. I make sure I don’t

go too long without eating and sleep early.

As the day waxes, my confidence returns.

I remember what I need to, see to the hens,

make notes in my diary, in which I tell

the whole story. Sometimes I start to fall,

but I catch myself. At the dam I walk

steadily, don’t fear falling. Back at

home I’m warmer, shed layers, resume

morning tasks and rituals, with enough

energy for the day. By myself I see the

years of faithful work to leave my legacy

of stories and insights alive behind me.

Among others I see their discomfort.

They don’t look at me. They forget

my place in the line-up of poets. I make

them nervous. Why? Maybe because

I look into Death’s face and am not

afraid. How does one find that

particular courage? It arrives in time

to be useful in the last years, but I

realize I’ve practiced going my own way

most of my life, since age twenty-one,

to nearly eighty-one. Not dismissing

urgencies that would keep me whole

and safe, not denying love when it

defied logic. Those who hated me? I

stayed away, and generally, they did, too.

I sometimes lose things or forget them,

but I’ve never forgotten to safeguard

my soul and keep it whole, no matter

what my circumstances are."

- From Judy Hogan's original poetry book "Shadows"

"Proust thought Time destroyed us,

those hidden memories our only

salvation. For me, Time allows

fulfillment, to come into my own,

to learn, to heal, and even to be

recognized and valued. There were

people who hated me, but they

didn’t stop me. My own body

slowed me down, reminded me

I had done well and to think of those

I love. I persuaded my friends

and my doctor to trust my way

of life, my faith in myself; to let

me continue my independent way.

My son and I learned to live

together. We lost some crops,

but harvested bushels of tomatoes.

I made spaghetti sauce and soup.

Now there are grapes to make

Muscadine jelly, pears to make

preserves. I do my work as a

writer, editor, teacher. I celebrate

Jaki, whom I first published

forty-five years ago. I will

teach poetry and story writing.

Like the moon’s slow, steady

increase of its light, I resume

my own life of work and love."

- From Judy Hogan's original poetry book "Shadows"

"I slowed down, did easy work, nothing

strenuous. The hurricane left us to mop

up and dry out. Sun came back, the better

to see the devastation. Here, where we

escaped the worst, life was almost normal

despite rivers that flowed upstream, the

milk we couldn’t buy, the flooded roads

we couldn’t pass. I wanted more work.

I made a list I’m crossing off. Something

in me wants serious work, to tell some

story more than poetry tells or my

diary. A new book then about aging

and adapting. There is more to tell

than I have admitted so far. At eighty-one,

how many women tell what it’s like,

to lose the capabilities we always assumed,

to have gates closed, but the mind still

open, still able to articulate paradox

and justice, when everything in the human

being or in the state works easily and

smoothly together, each part doing its

own work? Mine has been to write, tell

my mind’s story. I’ve written many books,

but there is still more to tell. I will."

- From Judy Hogan's original poetry book "Shadows"

"How do I describe my faithfulness to my

deepest knowledge, to what I see but

can’t easily reveal in words. I tried not

to be good as a child is good. I rebelled

against old formulas, trite words. I loved

Thoreau’s wisdom: “If I see someone

coming to do me good, I run for my life.”

I rejected that impulse to “do good.” Yet I

have always worked against evil when

I saw it blazing up in corporations, in

those fearful of rocking the boat, or who

were terrified to be seen as bad, as trouble-

makers. So I’ve been castigated, dismissed,

written off. It hasn’t been so bad. Some

tender hearts have loved me, and even

tough-spirited strangers have helped me

out. I have a few fans of my books. I

don’t need acclaim, but I do need to feel

loved and acknowledged by those I love

and trust, those who can see with clear

eyes who I am, what I care about. I’ve

been told many times that what I want

is impossible, will never happen. They

say life isn’t like that. You don’t get what

you wish for. In short, the power of evil

is too great. I don’t give up, however,

and then people love me. Things begin

to change. What my skeptics have

forgotten is the power of transformation

and what love can do when it’s unleashed,

when we see clearly, when other people’s

minds open like a book that wants to be

read. I can’t make that happen. I can’t

stop it. I can, however, give it my

gratitude and let it go to work."

- From Judy Hogan's original poetry book "Shadows"

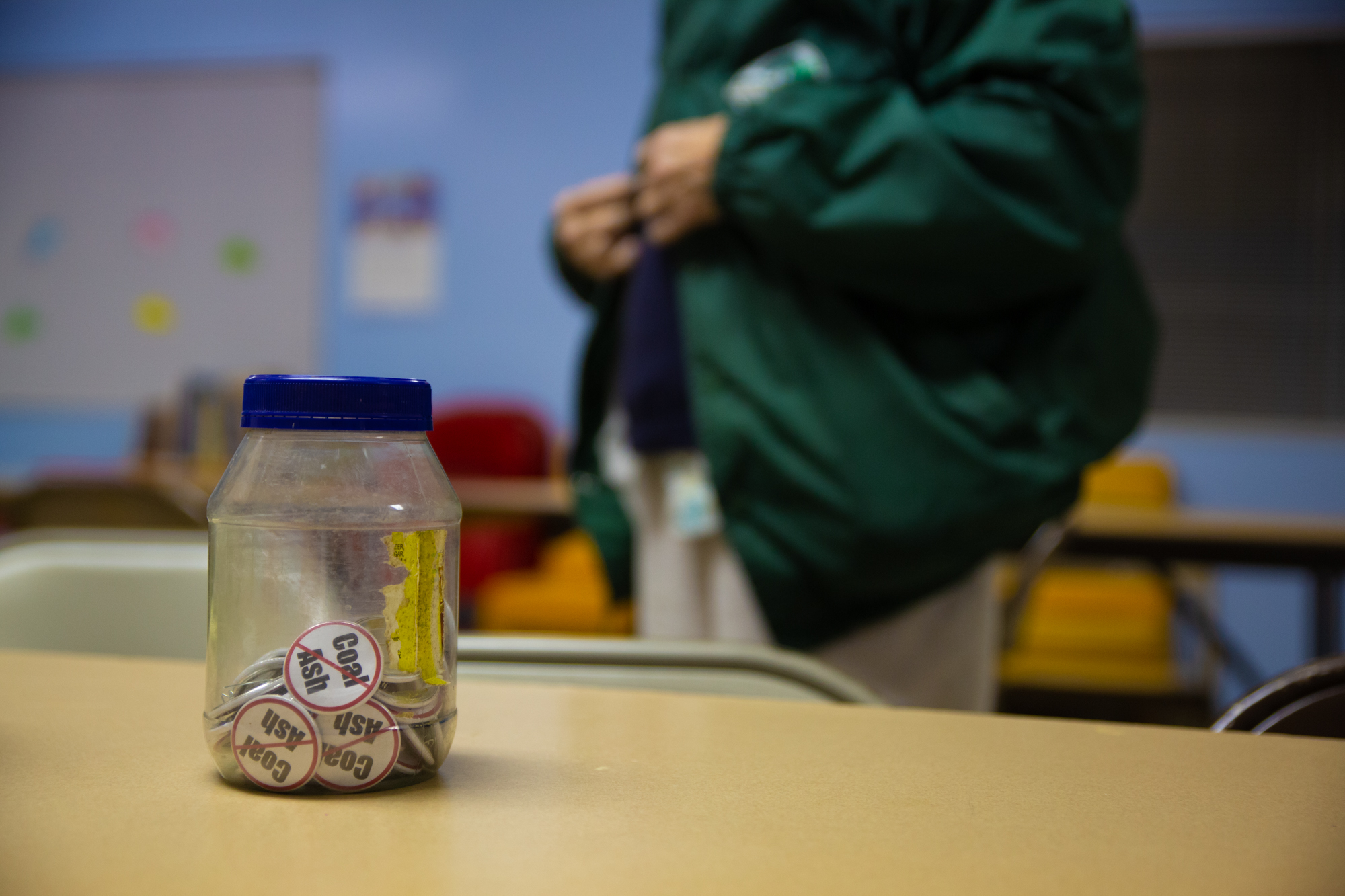

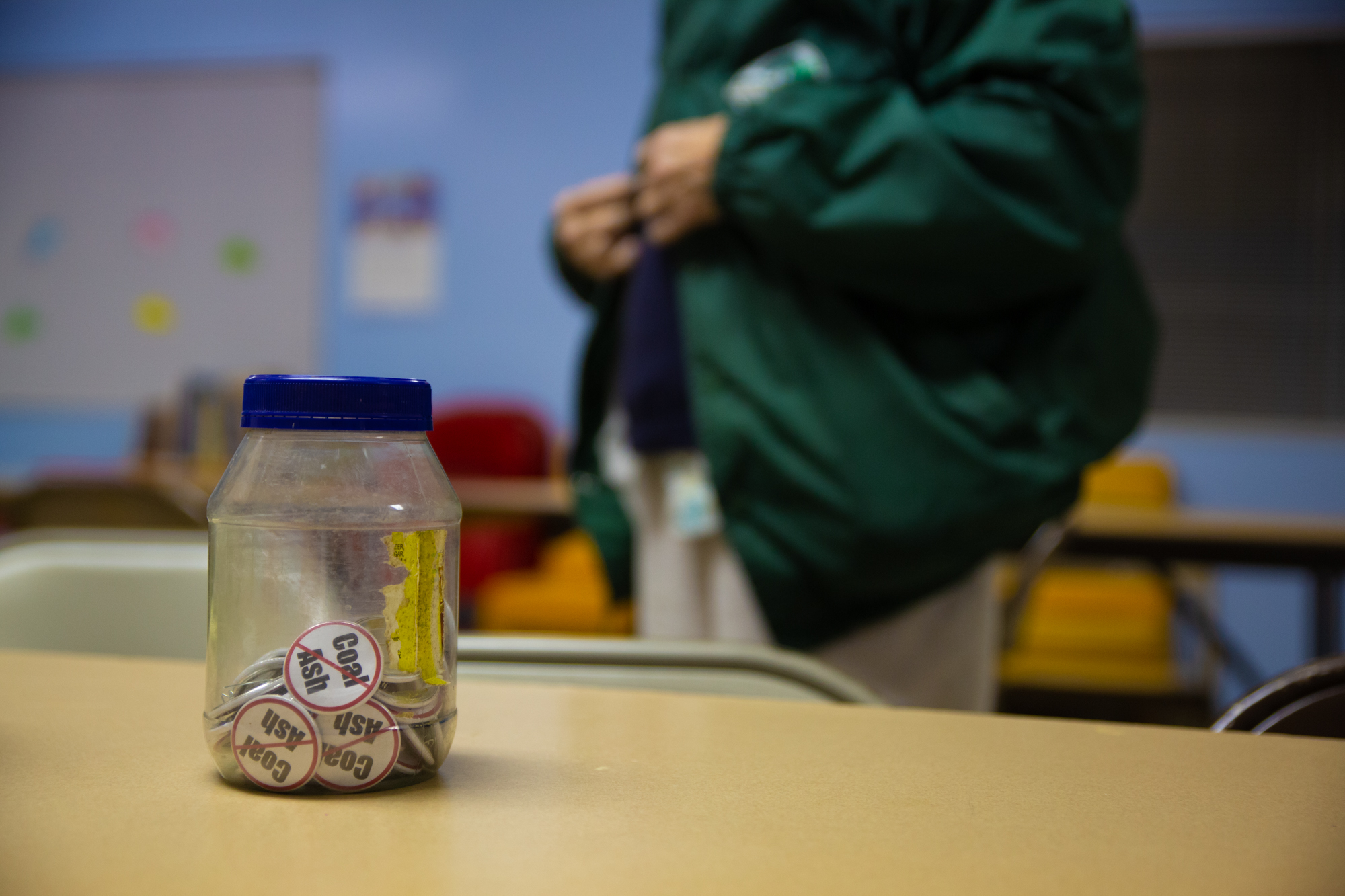

"Milosz helped me see, at age

eighty-one, that our worship of science

and technology, our allowing a dictator

to be elected president, is killing us off.

The big electricity corporation has brought

us a present we couldn’t refuse of seven

million tons of poison. They say they’ll stop

now. They’ve done enough damage. Instead,

they’ll burn the coal ash again and kill us

faster. No one stops them. People are

getting sick. They don’t want to fight

any more. They forget: when we fight, we

love each other. We can live with our

differences. Black, white, and Hispanic;

church-goers and non-church-goers.

Andrew says, “You’ve won a victory.

Have a victory party.” Rhonda says,

“You’re defying the doctors. I predict

you’ll have a stroke.” She’s angry at her

body’s weakness, and at me, for trusting

myself and challenging doctors, our techno-

masters in a sickening world. The human

body knows how to heal itself. Instead, they

give us pills and then more pills, and the

body then is truly sick, won’t fight any more.

Milosz lived under the Nazis, under Stalin.

He fought and he survived. I, too, am

fighting, and I, too, am surviving. Love

can conquer. Give it a try."

- From Judy Hogan's original poetry book "Shadows"

"Even love has its misunderstandings.

Sometimes my son and I knock heads.

We’ve learned to let go when arguments

go nowhere. Everyone has her own world

view, her own life story, fears, and dread.

Agony is human, but so is joy. We watch

the exultant eagles join the circling vultures.

For one, it’s work-related, for another, it’s

ecstatic. When our hopes and desires

merge, worry disappears. When pain

returns, we are constrained to work free.

I write my troubles down, the better to let

them go. When they reappear, I’m

prepared. We all learn as fast as we can,

which means some more slowly than others.

A lot depends on our heritage and even

more on work we’ve already done to cope

when people hated us, when our loved ones

turned their faces away. The late years

lead to a homecoming or some call it a

home-going. We have some say-so. For

me, there are many rewards in this last

stage, which Erik Erikson called “Ego

integrity versus despair.” We find rewards

for our self-defense, our ability to listen

and give a helping hand. People we

scarcely knew turn up to help us. A young

woman wants to study me for clues to

living a benign life as a freedom-fighter.

Another woman in her middle years is

drawn to my relaxed humor. Most terrible

things draw our tears, but some that can

wrench us later make us laugh. My

doctor, as I eluded the medicines and

survived, calls me Trouble, but she’s

smiling. Another older woman says we’re

both eccentric, but a good eccentric. My

son is learning to protect garden spiders,

cherish poetry, and love my homemade bread.

I still walk without a cane, urged upon me five

years ago. Some work I’ve let go. I rest more,

but I do all I can do–gratefully. Look around:

I have students and friends. I’m cherished by

those I want to cherish me. I’m alive and writing

down what my last years are like. Already I

inherit that persistence I fore-see in my shadow

after I’m gone. She’ll be okay."

- From Judy Hogan's original poetry book "Shadows"

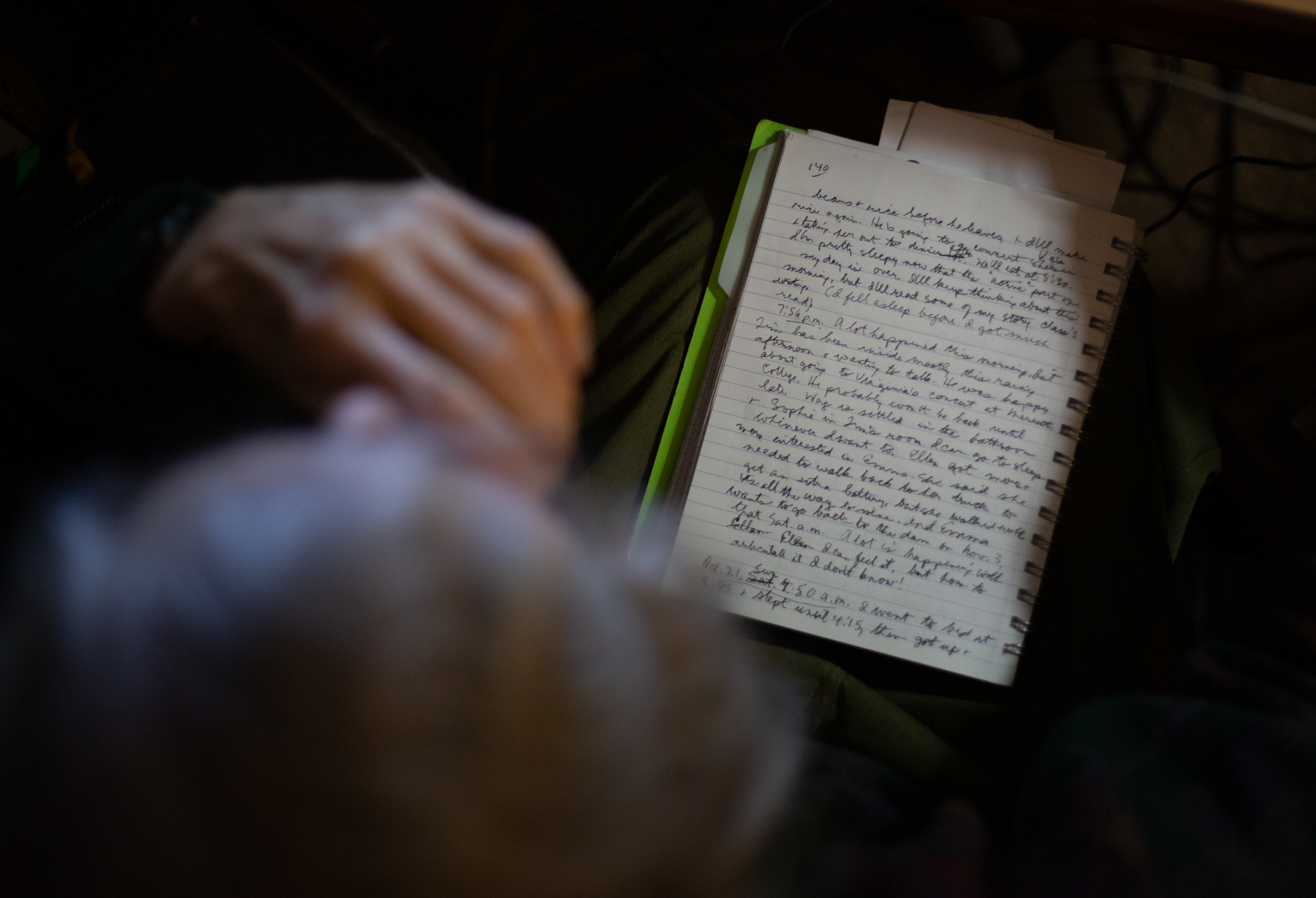

Day by Day

Dr. Andrew Ross was diagnosed with ALS in April 2017, and in August 2018 he decided his ALS was bad enough that he needed around-the-clock care. He moved out of a house and into an apartment in Chapel Hill, N.C. Ross now receives care mostly from Lora Bradley, employed by HomeWatch Caregivers. His ALS has been described by doctors as “especially aggressive”, but Ross has a very positive attitude.

On Oct. 9, 2018, Lora Bradley helps Dr. Andrew Ross walk across his apartment in downtown Chapel Hill, NC. Dr. Ross was diagnosed with ALS in April 2017, and in August 2018 he decided that his ALS was bad enough that he needed around-the-clock care. Andrew now receives care mostly from Lora, employed by HomeWatch Caregivers, and due to the debilitating nature of ALS and the amount of time they spend together, Bradley and Dr. Ross have a very intimate relationship.

“We are like mother and son,” Ross says. “She takes care of me while I slowly lose control of my body.”

Dr. Ross keeps this ALS band on his wheelchair as a reminder to just take his life day-by-day. The average life expectancy for people living with ALS is three to five years, but Dr. Ross’s is especially aggressive and progressing more quickly.

“With ALS, every day is a new challenge for us, and we have to come up with innovative ways to solve whatever is coming next based on how Andrew’s body is working,” Bradley says. “He keeps me on my toes!”

Bradley often transports Ross in a big body sling when he is not strong enough to walk. He uses the sling in order to use the restroom and be lifted into his bed at night.

“ALS doesn’t stress me out,” Dr. Ross says. “The fact that I’m dying doesn’t stress me out. I can’t think about that because it seems too far out. All I know right now is that I’m waking up tomorrow and doing something, and I take each day as it comes. But I do feel like I’m living someone else’s life.”

Irene Zhu, a UNC Chapel Hill senior planning on going to school to be a physician’s assistant, walks with Dr. Ross through the floors of his apartment complex on the evening of Oct. 25. On every floor of the apartment, the walls are filled with original art donated by residents of the building, forming a sort of gallery. Before being diagnosed with ALS, Dr. Ross was a photography professor at Radford University in Virginia, and still thoroughly appreciates art.

Most weeks, Dr. Ross receives new technology to cope with his ALS, which is why Rebecca West dropped by the apartment with a new breathing machine. Lora Bradley sasses Dr. Ross while West jokes about death.

“There are so many people going in and out of my house all the time, and I have so many caretakers. Not all of my caretakers are as great as Lora is either. I’ve had to fire some of them. Because of this, I never know where things are in my own house. So I don’t feel like this is my home anymore. I’m just living here.”

Bradley helps Dr. Ross shower every other day.

“My privacy is the thing I miss the most,” Ross says. “My whole life in all of its forms is wide open for the whole world to see. That’s what the disease has made me give up.”

Andrew Ross talks to his mother, Mary, about her recent visit with Andrew’s father on Andrew’s behalf to Radford University. Andrew felt too sick that day so didn’t go. Mary Ross shows Andrew a past photo they all took at the university together, and Dr. Ross tells his mother about the people she spent time with this time around. Mary Ross has Alzheimer’s and doesn’t remember the people she met, so Dr. Ross is very patient with her.

Mary Ross does her best to entertain her son by rubbing his feet during his monthly ALS check-up at the Duke ALS Center in on Nov. 8. She can’t do a lot for him, but still dotes on him a lot.

Mary Ross and her husband John look on concerned as a doctor attempts to figure out why Dr. Ross has been coughing so uncontrollably in the last week. Dr. Ross doesn’t believe that his lungs are getting weaker or that his ALS is the reason he is coughing, but the doctors say that it is.

Dr. Ross goes to bed at the end of the day with oxygen to help him breathe more easily and comfortably.

“At night is when I feel most helpless,” Andrew Ross says. “I don’t have the ability to move, and I don’t have my phone or computer with me, which helps me communicate. People also can’t hear me with this mask on, and my caretaker is in the other room at night. So there are a lot of things that could happen at night, but I wouldn’t be able to do anything about it.”

Mothering Mother

Ellen Tobin reflects on the impact of her dying stepmother as she mothers children in her own child care in Jan. 2021 in Charlotte, N.C.

Ellen Tobin reads an email update from her sister, Mary, on Jan. 29, 2021, as she is about to get ready for the day. It reads,” I will be going to see Mom today. I can't believe that I'll finally be able to step inside to see her, hold her and pray with her. I will treasure every minute that I can sit by her and say, ‘I love you’ and ‘Thank you.’”

Tobin’s stepmother, Ron’s, health has been declining rapidly after she was diagnosed with dementia a year ago. No visitors have been allowed into her memory care unit to visit during the past year due to COVID-19. Now, Ron Hurley has decided she doesn’t want to try to live anymore and is barely eating or drinking and won’t pick up the phone. It’s a big deal that Mary is finally being allowed in to visit her.

![Tobin works out at 5 a.m. the morning of getting the emotional email. “Exercising does give me extra energy and perspective to make me feel more capable, like now anything that happens [with Ron], hopefully I can better handle the da](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a552064f9a61e74e2121c2c/1694016248302-8FSRK63AD8TSHSPSTRPL/ChildCareStory-2.jpg)

Tobin works out at 5 a.m. the morning of getting the emotional email.

“Exercising does give me extra energy and perspective to make me feel more capable, like now anything that happens [with Ron], hopefully I can better handle the day. It's hard for me to articulate to anybody the impact she had on me,” Tobin says. Tobin’s own mother died from cancer when she was a teen. “Something about the person you could always count on no matter what not being there anymore. And who has loved you unconditionally and has known you your whole life. She’s one of the rocks I always stood on. I’ll miss her. She just made such a big impression on me. I think she was just such a welcoming, compassionate, intelligent, caring person, and when she entered my life, challenged me as probably someone older than a 16 year-old.”

Tobin meditates every morning for ten minutes before she welcomes babies into the child care she runs out of her home. She has been running her child care for over a decade, after raising six children of her own.

“I hope that I translate some Ron Hurley traits into my mothering because I think those are super important,” Tobin says. “I feel like I’m mothering these babies. I’m invested in what they learn. I’m not just giving them a bottle to pacify them. I care that they are potty trained. I care that they are self-soothing. I care that they don’t turn into monsters by the age of two because that will follow them for a long time. But I’m also aware that whatever the parents do is going to trump what I do. This child care is a very important place, but not the most important.”

Sarah Haverland waves hello as she drops off her daughter, Elizabeth, at Tobin’s child care on Jan. 29, 2021. The work day begins.

![On Jan. 29, Tobin starts crying again thinking about her stepmother so close to death. “By observing Ron and how she treated me, I thought, ‘Wow, I feel like a real person.’ You know, I was a bit older [when she came into my life], so it's not fai](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a552064f9a61e74e2121c2c/1694016254337-X5PAKJC6H54DL7GN4FBG/ChildCareStory-5.jpg)

On Jan. 29, Tobin starts crying again thinking about her stepmother so close to death.

“By observing Ron and how she treated me, I thought, ‘Wow, I feel like a real person.’ You know, I was a bit older [when she came into my life], so it's not fair to say my mom wouldn't have done that or didn't do that. [My own mother] was just very stoic and didn't have the space or the time. And by the time I was fourteen, my mom was very sick. By the time I was 16, she had died. So when Ron entered in, and she was so emotionally adventurous and a school psychologist and talking about things my mom would never have talked about, and it was kind of cool. Not that I got a second chance [at a mom], but I had frosting on the cake with Ron.”

Tobin laughs at Larkin Flanagan, one of the children in her child care, while she goes on their daily walk. Macy Harrison, Nellie Pfeiffer, and Elizabeth Haverland sit in the stroller. She usually either takes them to a playground or to see something new going on in the neighborhood, like construction or big trucks.

“So much of it can be about me to a point, but it's so much more meaningful to focus on the next generation,” Tobin says. “Other mothers might not say that. They might feel like there should be a lot more balance, or they're not as committed to being a mother. But for me, I feel like for everything I've done in life, that's the reason for everything.”

Tobin scolds Larkin Flanagan after she wasn’t playing nicely with one of the other children in the child care. She puts her in the “Thinking Corner” for a few minutes before asking Flanagan to apologize to her friend.

“All the effort and time you put in when they're young matters, because you have to remember that kids are in our lives as adults for so much longer than they are children,” Tobin says. “Eighteen years is very short compared to a lifetime.”

At the end of the day, Tobin waits with the kids from her child care at the front window as they wait for their parents to come pick them up. Every time a child moves on from the child care, Tobin writes a letter to the family, who she works to develop a close relationship with over time.

“I feel like it's really the same feeling I have when each one leaves, you know, it's not even a variation of it,” Tobin says. “My letter to the families always says, ‘Well, at this point, words just diminish my feelings for your family. I can only hope that day to day over the past years, you felt the genuine love we have for you. My primary hope is that your child developed a core belief that: (1) they are loved by many, (2) they belong, (3) they are capable, and (4) they are so, so special. The world will teach them all the rest. Life has been more fun with your child in it. Thanks for sharing so much of your lives with us.”

![“Ideally as an adult going through [losing a mother figure], you can rationalize more things and intellectualize,” Tobin says. “Better equipped to cope. Not that it’s not going to hurt. It will when [Ron] dies. And it’s going to set off old alarms.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a552064f9a61e74e2121c2c/1694016259311-R8AKP5ZBVH5V6QB9R1IX/ChildCareStory-9.jpg)

“Ideally as an adult going through [losing a mother figure], you can rationalize more things and intellectualize,” Tobin says. “Better equipped to cope. Not that it’s not going to hurt. It will when [Ron] dies. And it’s going to set off old alarms. The “mother” and “loss” alarms. But it won’t take years and years to get through this time. And as a mother, I can hope I’m putting something good into the next generation of children while I’m going through it.”

![Tobin works out at 5 a.m. the morning of getting the emotional email. “Exercising does give me extra energy and perspective to make me feel more capable, like now anything that happens [with Ron], hopefully I can better handle the da](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a552064f9a61e74e2121c2c/1694016248302-8FSRK63AD8TSHSPSTRPL/ChildCareStory-2.jpg)

![On Jan. 29, Tobin starts crying again thinking about her stepmother so close to death. “By observing Ron and how she treated me, I thought, ‘Wow, I feel like a real person.’ You know, I was a bit older [when she came into my life], so it's not fai](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a552064f9a61e74e2121c2c/1694016254337-X5PAKJC6H54DL7GN4FBG/ChildCareStory-5.jpg)

![“Ideally as an adult going through [losing a mother figure], you can rationalize more things and intellectualize,” Tobin says. “Better equipped to cope. Not that it’s not going to hurt. It will when [Ron] dies. And it’s going to set off old alarms.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a552064f9a61e74e2121c2c/1694016259311-R8AKP5ZBVH5V6QB9R1IX/ChildCareStory-9.jpg)

Earls For Justice

Anita Earls ran to be the hundredth justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court in 2018 and won. This is a photo story done mostly on that election night. Earls stood on a platform of a 30-year tenure as civil rights attorney mostly in North Carolina, and frequently spoke about being a child in a mixed race family in an era where interracial marriages were illegal.

On the evening of Sunday, Nov. 4, Anita Earls sits in the pews of Union Baptist Church in Durham, N.C among fellow N.C. democratic candidates. The Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People invited democratic candidates they endorsed to each speak on their platforms for one minute. Anita Earls has been a civil rights attorney mostly in North Carolina for the last 30 years. She founded the Southern Coalition for Social Justice 11 years ago, and is now running to be the hundredth justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court.

“After my brother was murdered and the killer never prosecuted, I personally experienced what it means to not get your day in court,” Earls said. “If we are going to protect families and make communities safer, we need equal justice under law. People’s lives are impacted every day by the decisions that the Supreme Court makes. After 2016 in particular, I felt that the federal courts may no longer be a sympathetic avenue for civil rights claims. And state constitutions are rich and robust sources for protection of our rights. Our state Supreme Court can make a lot of decisions about things that impact their lives daily.”

A pile of abandoned voting day materials advocating for Anita Earls lays abandoned on a table at the North Carolina Democratic Party headquarters in Raleigh on election night Nov. 8.

“I became an attorney because I grew up in a mixed race family,” Earls says. “My father was black and my mom was white. When they met and fell in love in Missouri it was illegal to get married. As I was growing up, the Supreme Court decided a case that said those covenants cannot be enforced. So I overtime saw the law as a way that could be used to break down barriers. And I saw the role that lawyers could play in that. Crossing that racial divide was essential to our survival as a family, essential to my survival. And I think equally now, coming together to bridge that divide and fix our democracy is essential to our survival.”

On election day, Nov. 6, Earls sits alone in front of a food table before her “war room” party at a hotel in downtown Raleigh. The rest of her campaign staff are taking up the rest of the chairs in the suite doing work.

“I’m really nervous. I have no clue what I’m supposed to be doing right now. I have no idea how this works,” Earls says. “Am I supposed to call my opponent if I win? What is that timing like? Do I wait for her to call me? How long? What if she wins? I’m really in the dark here. I’m really not a politician.”

Anita Earls, Brenda Richardson, and Caroline Spencer, Anita’s campaign manager, laugh at a photo on Richardson’s phone of a nearby polling place in Durham. A sign at the location says, “They don’t want us to vote for Anita Earls.”

Anita Earls nervously watches the results from other state races come in on the television on election night, waiting for her own race to be called.

After Justice Barbara Jackson, Earls’ leading opponent called her and conceded, Earls, Caroline Spencer, and José Morales scream in celebration in their hotel “war room” in Raleigh, N.C.

“This is a moment I will never forget,” says Caroline Spencer, Earls’ campaign manager.

At the North Carolina Democratic Party headquarters in Raleigh, Earls is met with a vivacious crowd of supporters after her victory is announced as the 100th justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court.

Anita Earls takes the stage at the North Carolina Democratic Party headquarters as her supporters cheer below. Juju Holton and Caroline Spencer, who both worked on the campaign, shed tears and celebrate behind her.

“We have a president who believes that he can by executive order erase the 14th amendment to the U.S. constitution,” Earls says in her speech. “We have misguided misguided partisans in our state who believe they should impeach justices that don’t rule in their favor. I promise to resist partisan attacks on the judicial branch, which must remain independent and impartial in order for our democracy to succeed and thrive. Thank you for believing in the possibility that a civil rights attorney can run a state-wide campaign and win the trust of voters. Thank you for believing that you can make a difference because you have. And now, let’s move forward without fear or favor.”

Even after midnight on election night, Anita Earls doesn’t relax, despite her victory. She continues researching how undeclared races are being counted while she drinks champagne.

“In the words of Nelson Mandela, ‘After climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb,’” Earls says.

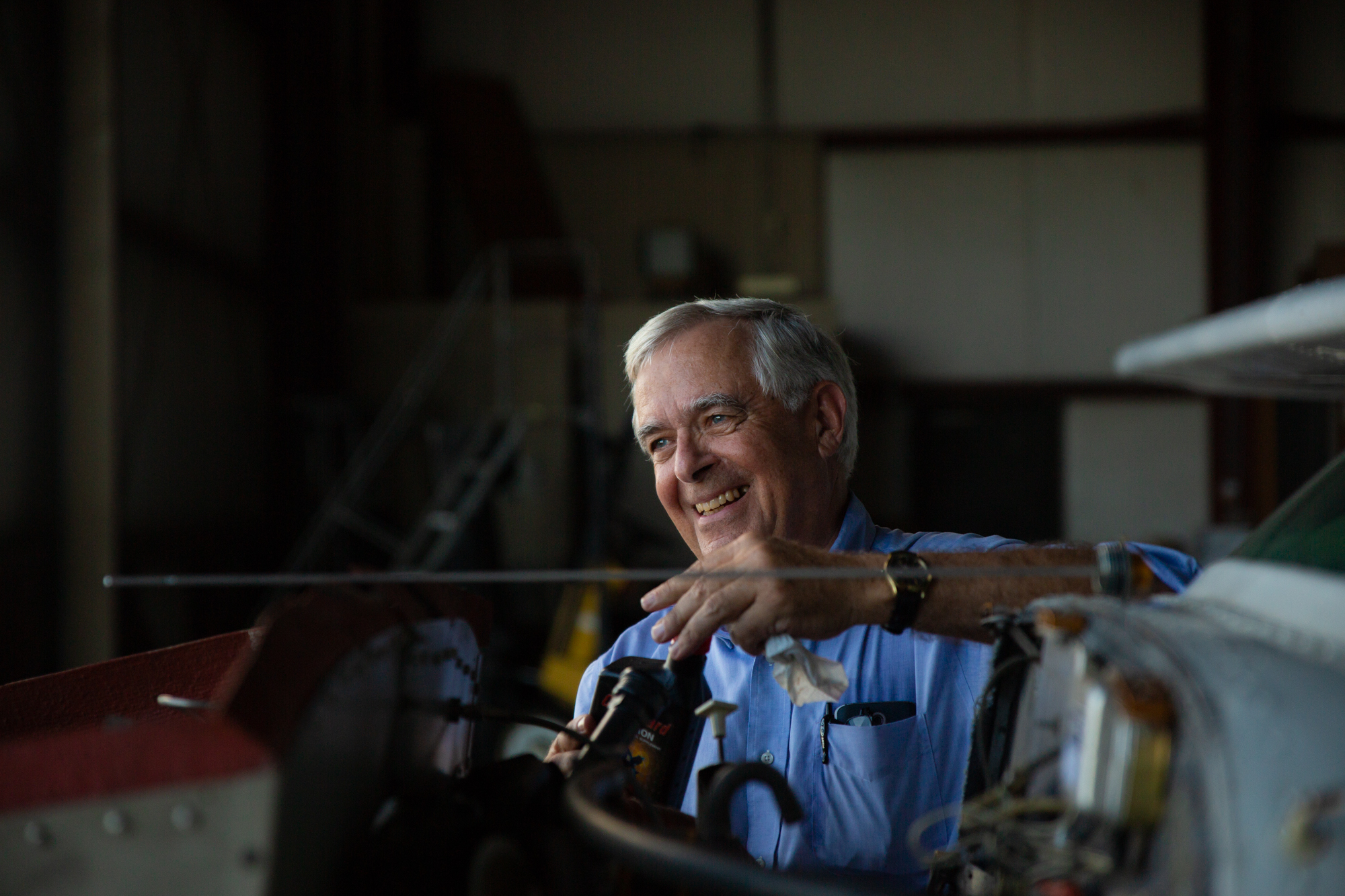

Hurricane Florence Takes Flight

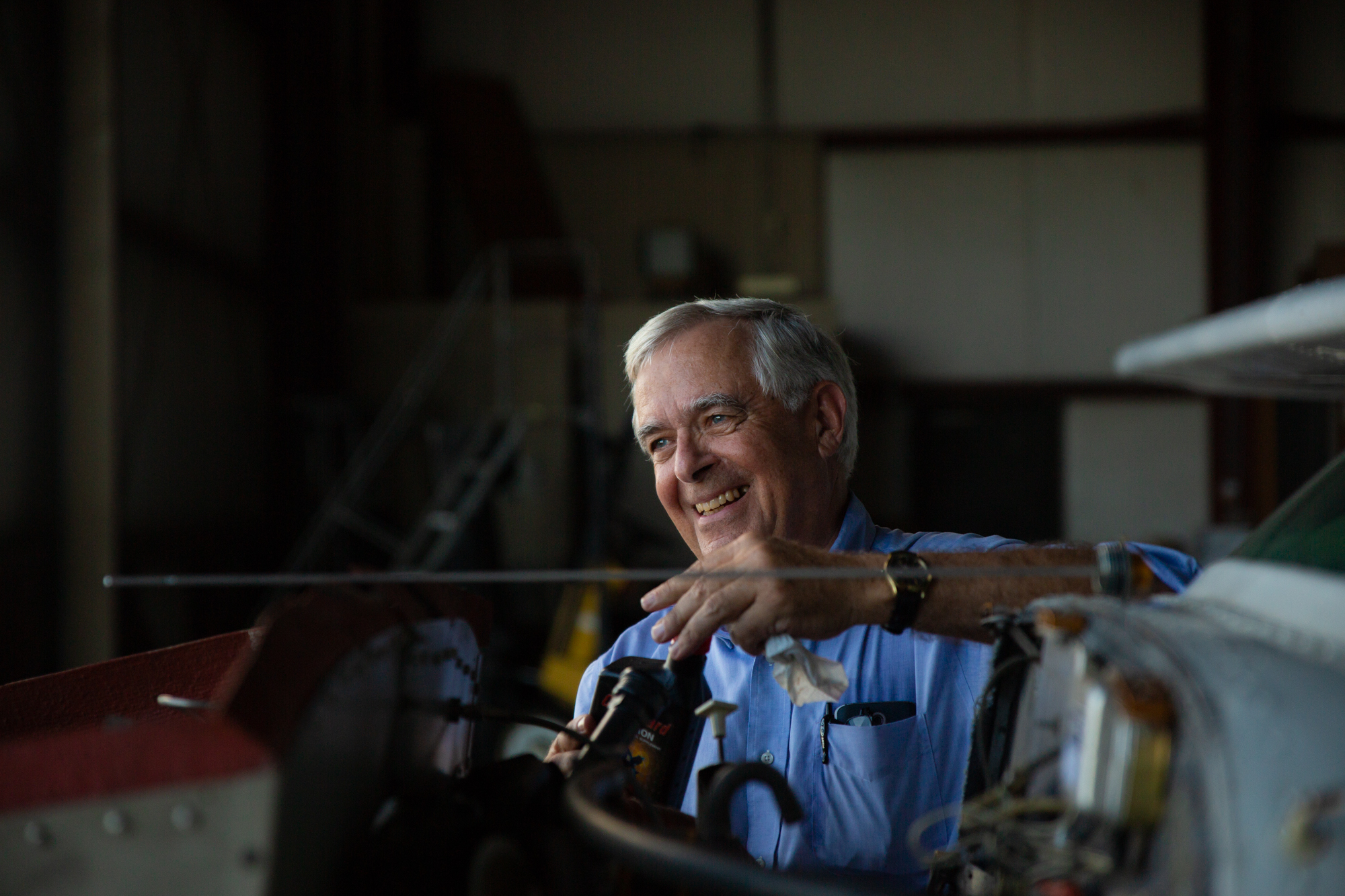

Steve Watkins, one of the longest-tenured flight instructors in the U.S., owns his own tiny flight instructing company called Watkins Aviation in Person County, N.C. He has clocked over 9,000 hours flight instructing – one of about one hundred in the country with this accomplishment. This is a story about Watkins and a hurricane that blew through.

On Wednesday, Sept. 12, 2018, Steven Watkins, one of the longest-tenured flight instructors in the U.S., flies above Person County, N.C. He has clocked over 9,000 hours flight instructing – one of about one hundred in the country with this kind of accomplishment. Watkins owns his own tiny flight instructing company, called Watkins Aviation, of which he is the sole instructor, and operates out of Person County Airport in Timberlake, N.C.

“The single biggest thing is freedom,” Watkins says. “There’s a sense of escaping the rest of the world when you’re up there. A lot of my students over the years have not liked their jobs, but then they come out here flying, and they don’t think about anything but flying. So, it’s an escape. For me, it’s not an escape of pressure, but an escape into my own little world. And in a lot of ways, it’s very peaceful… My workplace is the sky.”

In preparation for Hurricane Florence hitting the east coast, Watkins flies one of his planes back from South Boston, V.A. Watkins and his partner in the plane’s ownership, Carl Chambers, push the plane inside the hangar so that it doesn’t get damaged due to sporadic hurricane storming.

“I started flying when I was 14,” Watkins says. “A dentist by my family farm taught me. He didn’t give me formal flying lessons; he just brought me up and said ‘Here are the controls.’ The airplane in those days ran for $8 an hour and $4 for the instructor. He was just a nice guy and bought planes and made them available for people to use. Today, I charge $60 for the instructor, which is me, and $130 for the plane per hour, which sounds expensive, but I try to keep costs low. I’m paying it forward.”

Watkins changes the fuel on the plane he uses the most for instruction, a Cessna 150.

“I love this work. I’m 68, but to me, retirement is something you do if you don’t like your job. Most of retirement got rolling when manufacturing took off in the teens and twenties and so people would go to work and they’d work hard at manufacturing…. In my world, if you work for somebody else and it’s a job and you get paid and you go home on the weekends and you do what the average person does, then retirement is something to look forward to… I’ve been fortunate my entire life, pretty much, to do things I wanted to do on my own schedule. And if you like what you do, why do you want to quit?... So depending obviously on physical health and mental health, I figure I’m pretty much going to flight instruct for at least another 8 or 10 years. Maybe longer, as long as I possibly can. I can’t really imagine retiring anyway. It’s never been on my radar.”

On Thursday, Sept. 13, Watkins warily watches the weather forecast as Hurricane Florence is predicted to hit the N.C. coast hard.

“I’ll likely have to cancel my students for the next couple days,” he says. “Also have to make sure all the planes are tied down or put in the hangar.”

Watkins watches the weather outside when his daughter Carey Anne comes to visit. Once he cancelled his flight students due to the hurricane, Watson spent a lot of time sitting in the airplane hangar building a plane for his daughter.

“He doesn’t like to admit it, but I think tinkering on planes is my dad’s favorite part of his job,” Carey Anne Watson says. “When my brother and I were little, he had a plane in our garage and all you could ever see was the fuselage. He just tinkered away on it but never finished it.”

On Friday, Sept. 14, Watkins parks himself in the airplane hangar for the day while Hurricane Florence dumps rain outside. He tries for hours to fix a shattered work light.

“I see it, so it’s my responsibility to take care of it, regardless of how it got broken,” Watkins says. “I can learn something from this... If we decide we are spiritual beings living in a human existence, maybe the suffering isn’t the important lesson. Like this light situation is frustrating. I think I also bought the wrong bulbs to fix it. Maybe the lesson is what you learn from what goes on in your life instead. I hear people say that everything happens for the best, and I don’t particularly believe that, but I believe there’s something to be learned from all things and people in all situations.”

By the time Saturday, Sept. 22 rolls around, Steve Watkins is in the swing of giving flight lessons again after Hurricane Florence passes. On this day he is teaching Douglas Appleton, who is training to get his private pilot’s license.

“The thing about teaching flying is that you tend to bond with a lot of your students,” Watkins says. “More than other professions. You spend more time with them and you share a common interest… I feel fortunate to be both an instructor and a mentor. About 20 years ago I started questioning what makes me run. And it’s not money. Some days I wish it was. The greatest sense of fulfillment comes from helping other people… One of the things I tend to believe is called the law of reciprocity. My belief in life is that if you help enough other people, you’ll be rewarded. If you make it about you, life can get pretty miserable. That’s why I teach.”